Italian Pasta guide: all you need to know

Italian pasta is one of the world’s most loved foods, and one of the most misunderstood.

From spaghetti and fettuccine to rigatoni, farfalle, tagliatelle, and lasagna, pasta shapes have shaped the history of Italian cuisine and found a place on dinner tables all over the world.

But what makes pasta truly Italian?

Why are there so many shapes?

When should you use fresh pasta instead of dried?

If you’ve ever wondered how to cook pasta the Italian way, or why your pasta and fagioli never tastes quite like it does in Italy, you’re in the right place.

In this guide, you’ll learn everything you need to know about Italian pasta: its origins, how it’s made, the difference between fresh and dried pasta, and how to use each type correctly in your own kitchen.

Before we dive into techniques and recipes, let’s start with the story of pasta, where it comes from and how it became the iconic food we know today. Italian pasta is more than just a quick meal. It’s a food shaped by history, geography, and tradition, where every detail, from the type of wheat to the shape of the pasta, has a purpose.

Let’s start at the beginning…

Origin of Italian pasta

Is pasta really an Italian food?

The history of pasta is fascinating and spans multiple cultures and centuries.

While pasta is now one of the strongest symbols of Italian cuisine, its origins are complex and influenced by several civilizations, including China, the Middle East, Greece, and ancient Rome.

According to historical documents, pasta appeared for the first time in Sicily around the 12th century, during Arab domination. It was known as itriyya and was made from durum wheat semolina. One of its greatest advantages was that it could be dried. Drying pasta allowed for long-term preservation and easy transport, making it an ideal food for travelers and sailors.

Within two centuries, pasta had spread throughout Italy. It became especially popular in Naples, where durum wheat was widely cultivated and the warm, dry climate was perfect for producing and preserving dried pasta.

As pasta traveled across regions and civilizations, each culture adapted it to local ingredients, traditions, and cooking methods, adding richness, diversity, and new recipes that we still enjoy today.

Fresh pasta vs dried pasta: what is the difference?

Pasta gained great historical importance when it became a food with a long shelf life, capable of sustaining people during famines and long journeys. This development is closely linked to the discovery of two different types of wheat: soft wheat and durum wheat, and to the unique ability of durum wheat to produce pasta that can be dried and stored for long periods.

Historians now agree that this breakthrough occurred during the medieval period, particularly in Sicily.

Climate played a key role in the cultivation of these two types of wheat. Durum wheat thrived in warm, dry climates, while soft wheat could also grow in cooler, northern regions. As a result, two different pasta traditions developed in parallel: fresh pasta made from soft wheat (often enriched with eggs to add structure) and dried pasta made from durum wheat.

Fresh pasta in sheet form, made with soft wheat and now known as lasagna, may descend directly from the Greek laganon and the Roman lagana. Dried, long-shaped pasta made from durum wheat, on the other hand, likely originated in the eastern part of the Roman Empire during the first centuries AD, with evidence of its presence in Sicily as early as the 9th century.

One of the most common questions about Italian food is whether fresh pasta is “better” than dried pasta. The truth is that they are simply different tools for different jobs. Both fresh and dried pasta have an important place in authentic Italian cooking.

Fresh pasta (pasta fresca)

Fresh pasta is typically made from soft wheat flour and eggs. Its texture is tender and delicate, with a richer mouthfeel than dried pasta. It cooks very quickly, usually in 2 to 4 minutes, and pairs well with butter-based sauces, cream sauces, delicate oil sauces, and light tomato sauces.

Fresh pasta traditions historically developed primarily in northern Italy, especially in the Emilia-Romagna region. Use fresh pasta to make baked lasagna, tagliatelle al sugo, tortellini in brodo.

Dried Pasta (Pasta Secca)

Dried pasta is made from durum wheat semolina and water. It has a firmer, chewier texture and a more pronounced bite. Cooking times vary by shape, typically ranging from 10 to 15 minutes.

Dried pasta pairs especially well with tomato-based sauces and robust oil-based sauces. Its origins lie in southern Italy, particularly in Sicily and Naples, where durum wheat and a warm climate made large-scale pasta drying possible.

Thanks to its low moisture content, dried pasta can be stored for a very long time, often up to two years, without losing quality.

Use dry pasta to make

- Spaghetti al pomodoro

- Pennette all’arrabiata

- Amatriciana

- Pasta alla norma

- Pasta e fagioli

Pasta shapes: the art of pasta sauce pairing

What pasta goes with your sauce?

Which shape works best with lentils, vegetables, or meat?

Have you ever wondered how to pair pasta correctly, so your dish actually works instead of falling flat? Some types of pasta hold sauces beautifully, while others don’t. It’s a common misconception that you can use any pasta shape with any sauce, but that’s not exactly how it works.

Why? Because pasta shape matters.

In this section, I’ll show you the basic rules for pairing pasta with the right sauces and ingredients. And if you’re planning to bake pasta, you can find everything you need to know in my guide to the best pasta shapes for baked dishes.

In Italy, pasta and sauce pairings come from centuries of regional tradition and experience. The pairing always starts with the pasta’s shape. Here are some golden rules to follow for a correct pasta-sauce pairing.

-

Look at the shape. How does the shape of the pasta interact with the sauce? The coils of fusilli and the ridges of penne trap sauce beautifully, while spaghetti wraps around it, and shapes like lumachine (snail-shaped pasta) hold it inside.

Even the smallest details can change everything: the pasta’s curvature, the depth of its grooves, the thickness of the sauce, and even cooking time and method, all play a role in the final result. -

The extrusion process: why texture matters. The way pasta is made affects how it behaves during cooking and how it feels in your mouth. Pasta extruded through Teflon dies tends to have a smoother surface and a firmer center, while bronze-drawn pasta has a rougher, more porous texture. That porous surface helps the pasta hold onto runnier sauces, while smoother pasta works better with rich, creamy, or “enveloping” sauces. Bronze-drawn pasta is often preferred because it cooks more evenly and is less likely to become overly soft if slightly overcooked.

-

The fork test: judging the “bite” of a dish. The first step is always tasting both the pasta and the sauce. The goal is balance. A rich, robust sauce like carbonara would overwhelm delicate capelli d’angelo (angel hair), while wide ribbons like tagliatelle don’t work well with the light consistency of garlic, olive oil, and chili (aglio, olio e peperoncino).

The idea is to match the intensity of the sauce with the “bite” of the pasta. Small shapes such as shells or ditalini pair well with sauces or preparations meant to be eaten with a spoon, where pasta, sauce, and other ingredients come together in a single bite. Ditalini, for example, are commonly used with pasta e fagioli (pasta with beans soup), minestrone (pasta and minestrone soup), and chickpea-based soups, where their small size allows them to blend perfectly with legumes and vegetables.

-

The correct cooking technique. When all the conditions for a romance between pasta and sauce are in place, the cook’s role is simply to help make the two inseparable. Italian pasta makers provide detailed instructions on how to cook each shape correctly, both on the packaging and on their official websites.

Quick pasta–sauce pairing rules

-

Match the weight: light pasta shapes pair best with light sauces; hearty pasta needs hearty sauces.

-

Consider texture: smooth pasta pairs best with smooth, creamy sauces, while ridged or textured shapes are designed to hold thicker, chunkier sauces.

-

Think regionally: traditional pairings often come from the same Italian region, where pasta shapes and sauces evolved together.

-

Finish in the sauce: always toss the pasta with the sauce for the final minute of cooking, never just spoon sauce on top.

-

Save the pasta water: the starchy cooking water helps the sauce cling to the pasta, improves texture, and can be used to loosen the sauce if it becomes too dry.

Pasta shapes and sauce pairing: quick reference table

|

Pasta shape |

Pasta name |

Sauce type |

Why it works |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Long, thin |

Spaghetti, bucatini, linguine, vermicelli, angel hair |

Light oil-based sauces, simple tomato sauces |

The sauce lightly coats each strand without overwhelming it. |

|

Long, flat |

Fettuccine, tagliatelle, pappardelle |

Cream sauces, butter sauces, meat ragù |

The wide surface area supports heavier, richer sauces |

|

Short tubes |

Penne, rigatoni, ziti, tortiglioni, maccheroni, paccheri |

Chunky meat or vegetable sauces |

Sauce gets trapped inside the tubes and clings to the surface |

|

Ridged pasta |

Rigatoni rigati, Penne rigate |

Thick, textured sauces |

The ridges grip the sauce and hold ingredients better |

|

Shell shapes |

Conchiglie (shell), Lumache (snail) |

Chunky sauces, baked pasta dishes |

The hollow shape “cups” the sauce and ingredients |

|

Stuffed pasta |

Ravioli, Tortellini, Cappelletti, mezzelune, agnolotti |

Butter-based or light sauces |

The filling is the star; heavy sauces would overpower it |

|

Sheet pasta |

Lasagna |

Layered meat, vegetable, or cheese sauces |

Flat sheets create structure and balance in baked dishes |

|

Twisted shapes |

Fusilli, cavatappi, gemelli |

Pesto, thick vegetable sauces |

The spirals catch sauce in every curve |

|

Small shapes |

Ditalini, Orzo, Stelline (pastina) |

Soups, broths, legumes |

Easy to eat with a spoon and blends well with other ingredients |

|

Short pasta |

Bow ties, orecchiette, radiatori |

Meat, cheese or vegetable sauces |

Their shapes catch sauce in folds and pockets |

Classic italian pasta dishes you can exercise with

- Pasta aglio e oglio

- Pasta alla puttanesca

- Pasta alla amatriciana

- Cacio e pepe

- Pasta alla carbonara

- Lasagne al sugo

Learn how to cook perfect pasta

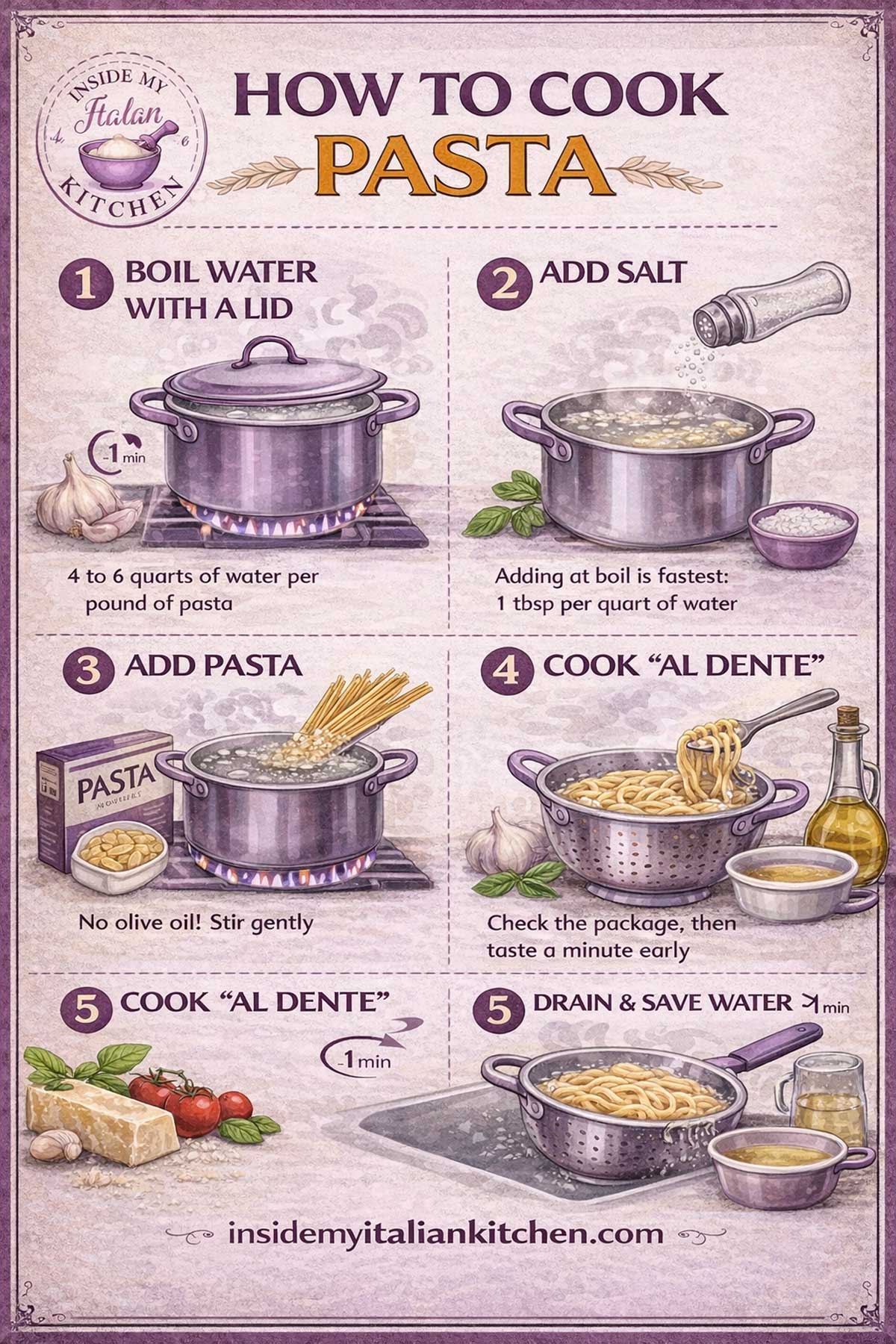

Cooking pasta is very simple, but a few key details make all the difference. How much water to use, how much salt to add, how long to cook it, and whether olive oil belongs in the pot or not.

This short guide will walk you through the essentials of cooking pasta the Italian way. Let’s start with the basics and then move on to the process.

How much water should I use to cook pasta?

Using the right amount of water makes cooking pasta easier and prevents sticking. A common Italian rule of thumb is: 1 liter of water for every 100 grams of pasta. In US measurements, that’s roughly: 1 quart of water for ¼ lb of pasta.

This amount allows pasta to move freely and cook evenly without needing to add more water later.

When should I add the pasta?

Always add pasta only after the water is fully boiling. Use a large pot, fill it with water, and bring it to a rolling boil over medium-high heat.

Once the water is boiling, add the pasta, never before.

How much salt to add (and when)

The “Pasta Rule” in cooking is 1-10-100: 1 liter of water, 10 grams of salt, 100 grams of pasta.

To make the water boil faster, place a lid on the pot. This helps the water reach a boil more quickly.

When to add salt is one of the most debated topics when cooking pasta. The truth is that adding salt to the water slightly raises its boiling point, which means the water may take a bit longer to boil. For this reason, the fastest way to get started is to wait until the water is boiling, add the pasta, let the boil return, and then add the salt.

Many people prefer to salt the water at the beginning simply because it’s easy to forget to do it after adding the pasta.

Does it make a big difference in the final result? Probably not. Your pasta will cook either way. The timing matters more in situations like camping at high altitude, where water already takes much longer to boil. If time isn’t an issue, adding salt at the beginning of the process is perfectly fine and often the most practical choice.

Do you need to stir pasta while cooking?

Yes, stirring is a good habit.

- It prevents pasta from sticking together

- It helps long shapes cook evenly

- It reduces the risk of water boiling over

- Give it a stir right after adding the pasta, then occasionally during cooking.

Olive oil in pasta water

Should you add olive oil to pasta water?

Contrary to popular belief, most Italians do not add olive oil to the cooking water. Olive oil does not prevent pasta from sticking together—that’s the job of enough water and proper stirring. Adding oil to the pot also wastes good olive oil, since it stays on the surface of the water and is drained away.

The only practical use for oil in the pot is to slightly reduce foaming after the pasta is added, but this can easily be controlled by lowering the heat. Save your olive oil for the sauce, where it actually adds flavor.

Cooking time

Cooking time is essential when making pasta. Manufacturers usually indicate an average cooking time on the package, and in most cases it’s a reliable guideline.

That said, cooking time can vary depending on the ingredients and the production method. For example, bronze-cut pasta often takes slightly longer to cook than pasta extruded through Teflon dies.

The best approach is always to taste the pasta near the end of the suggested cooking time and adjust based on texture, aiming for al dente.

Always save your pasta water

It can really come in handy. Pasta water contains starch released during cooking, which makes it incredibly useful for finishing and adjusting sauces. The starch in pasta water acts as a natural emulsifier, helping water and fats (like olive oil, butter, or cheese) bind together. This is what creates creamy, well-coated sauces in dishes like pasta alla carbonara or pasta con pesto, without adding cream.

If you’re tossing pasta directly in a pan with the sauce, a spoonful of pasta water helps prevent sticking, keeps the pasta moist, and allows the sauce to coat evenly instead of drying out or burning. Pasta water can also be used to thin overly thick sauces, enrich risottos, or even replace plain water when making bread or pizza dough, adding flavor instead of wasting it.

What “al dente” means

The explanation behind the term al dente is simple: it describes the ideal texture of pasta.

Cooking pasta al dente isn’t just a personal preference or an Italian obsession, it’s a fundamental principle of good pasta cooking. At this stage, the pasta is tender on the outside but still slightly firm at the center, giving it that satisfying “bite.” Reaching this point depends on a few key factors: the type of pasta, the cooking time, and the right balance of water and salt. When everything comes together, the result is pasta with better texture, better flavor, and a much more enjoyable eating experience.

Why Italians care

Italians care deeply about cooking pasta properly because food is an essential part of everyday life and culture. This attention to detail is a tradition passed down through generations. In Italy, people care about ingredients, how they are grown, how they are processed, and how they are cooked. Nothing is left to chance, and nothing should be overlooked when eating, because food is considered the body’s first form of nourishment and care.

Is pasta al dente healty?

Pasta cooked al dente naturally encourages you to chew more. This extra chewing stimulates saliva production, which contains enzymes that begin breaking down starches right in your mouth. By the time digestion continues in the small intestine, the starch is already easier to process.

There’s another important benefit: when pasta is cooked al dente, the starches are not fully gelatinized. This means they are digested more slowly, leading to a slower release of glucose into the bloodstream. As a result, al dente pasta has a lower glycemic impact compared to overcooked pasta.

Slower digestion also helps you feel full longer. That prolonged sense of satiety can reduce unnecessary snacking and overeating, supporting better portion control and overall balance.

Common errors people make cooking pasta

When to add pasta

We’ve all seen those viral videos where people add pasta to cold water and let it cook together. I’ve even seen people do this in real life—and yes, it gives me chills. Before adding pasta, your water must be at a full boil. Never add pasta to cold water and then heat it. Pasta cooked this way turns gluey, sticky, and unpleasant.

Unless your goal is to glue tiles to your floor with overcooked pasta, don’t do it. For pasta’s sake.

Cooking pasta in a slow cooker

The same goes for cooking pasta in a crock pot. Just… don’t. Pasta needs boiling water and movement to cook properly. Slow cookers remove both, resulting in mushy, overcooked pasta.

Some traditions are worth breaking. This isn’t one of them.

Break spaghetti

Every time an American breaks spaghetti, an Italian gets upset. This is not a stereotype. This is a rule.

Spaghetti should never be broken. Add them to boiling water, wait about 2–3 minutes, then gently push them down with a fork as they soften.

This is not a drill.

Do not break them.

DO. NOT. BREAK. THEM.

Did I mention you shouldn’t break spaghetti? 😉

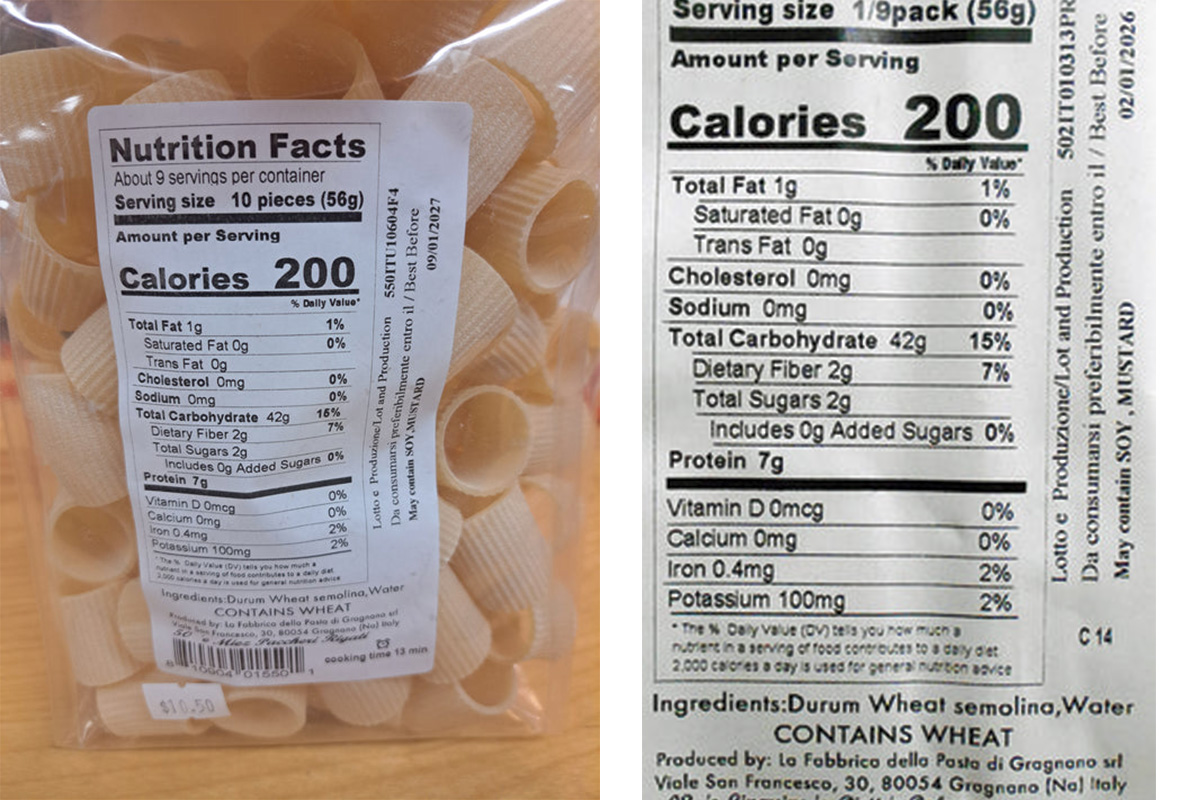

How to recognize real Italian pasta

Many Italian pasta brands are well known around the world, but a lot of people don’t actually know how to recognize whether a pasta brand is truly Italian. Brands like Rummo, La Molisana, Pasta di Gragnano, Barbieri, and Cavalier Giuseppe Cocco are among the most respected names in Italy and are also widely exported to the United States. Alongside these, there are many smaller Italian producers that don’t invest heavily in advertising but still make excellent, high-quality pasta.

One of the easiest and most reliable ways to identify real Italian pasta is to read the ingredient list. Traditional Italian dried pasta is made with just two ingredients: durum wheat semolina, water. That’s it.

Italian pasta is not enriched, and it does not contain additives, vitamins, or unnecessary extras. If you see a long ingredient list or added enrichment, you’re not looking at traditional Italian pasta. Instead, it may be an Italian brand producing pasta with American flour or in a U.S. facility.

American semolina flour is very different from Italian semolina, which is why cooking the same brand, produced in different countries or facilities, can lead to noticeably different results in texture and performance.

Good Italian pasta relies on high-quality wheat, careful processing, and slow drying, not on added ingredients.

Funny facts about pasta

- The word “pasta” comes from the Italian for paste, meaning a combination of flour and water,

- Spaghetti Bolognese was actually not invented in Bologna, Italy.

- There are more than 600 pasta shapes produced worldwide.

- October 17th is National Pasta Day.

- Thomas Jefferson is credited with introducing macaroni to the United States.

- Marco Polo did not introduce pasta to Italy. Contrary to popular belief, pasta was already used in Italy before Marco Polo’s travels to Asia.

- In Italy, pasta is often eaten as a first course, or primo, not as a main dish.

- According to Guinness World Records, the longest strand of spaghetti measured 10,776 ft and was made by Aloisio Fontana in Italy.

- The first ever pasta production line was made in Naples in the early 19th century.

- The first American pasta factory was opened in Brooklyn in 1848 by a Frenchman named Antoine Zerega.

- The average Italian eats more than 51 pounds of pasta every year.

- The average person in North America eats about 15-20 pounds of pasta annually.

- There’s a museum dedicated to pasta in Rome. It’s called the “Museo Nazionale della Pasta Alimentari”.

- Italians never use a spoon and a fork when eating spaghetti. This is an American habit.

- The art of pasta making is a family tradition in Italy and recipes are passed down from generation to generation.

- Ravioli was first created in the 14th century.

- Lasagna, one of the most popular types of pasta, comes from Italy and it’s believed to be one of the oldest types of pasta.

- Carbonara pasta does not actually include cream – the creamy sauce is made from eggs, PEcorino Romano cheese, guanciale (cured pork cheek), and pepper.

- The first pasta machine was patented in 1600 by Cesare Spadaccini.

Spaghetti, penne, fusilli, rigatoni, tagliatelle.

No. Rinsing removes the starch needed for sauces to bind to the noodles.

Al dente, which means “to the tooth” in Italian, is the ideal consistency for cooked pasta.

Water should taste like the sea; generally 10g of coarse salt per liter of water.

Starchy pasta water adds flavor, thickens sauces, and helps them cling to the noodles.